Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

This is an operation to remove the gall bladder using key-hole surgical techniques.

Here are explained some of the aims, benefits, risks and alternatives to this procedure (operation/treatment).

Please ask about anything you do not fully understand or wish to have explained in more detail.

What is the Gall Bladder?

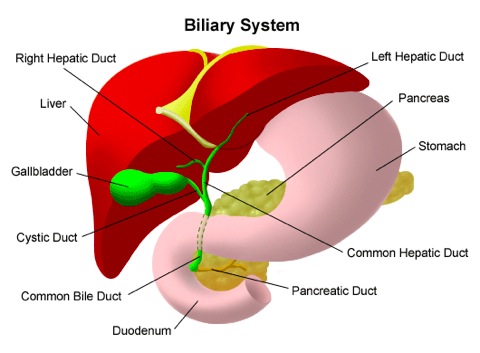

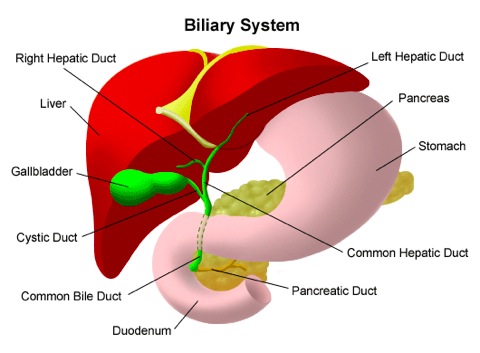

Your liver has many functions, one of which is to produce a substance called bile. This green liquid drains from the liver to the intestine via the bile duct (see diagram below). The gall bladder is a small reservoir attached to the side of the bile duct where bile can be stored and concentrated between meals. When we eat, particularly fatty foods, the gall bladder contracts and empties extra bile into the bile duct and then into the intestine to mix with the food. Bile has many functions, one of which is to allow us to absorb fat. The gall bladder sits just under the liver, which is in the right upper part of the abdomen, just under the ribs.

Why might I need my Gall Bladder removed?

Usually this is because it is giving you pain due to gall stones. These small stones form in the gall bladder and can cause a range of problems including pain, jaundice, infection and pancreatitis. They are very common but do not always cause symptoms. Gall stones that are not causing trouble can be left alone.

During the procedure (operation) itself

Before your procedure, you will be given a general anaesthetic. This is usually performed by giving you an injection of medication intravenously (i.e. into a vein) through a small plastic cannula (commonly known as ‘a drip’), placed usually in your arm or hand.

While you are unconscious and unaware your anaesthetist remains with you at all times, monitoring your condition and controlling your anaesthetic. At the end of the operation, your anaesthetist will reverse the anaesthetic and you will regain awareness and consciousness in the recovery room, or as you leave the operating theatre.

Four small holes (about 1cm long each) are made in the abdominal wall. Through these, your abdomen is inflated with carbon dioxide gas which is completely harmless.

Special long instruments are used to free up the gall bladder with its stones from underneath the liver and it is completely removed. This is all visualised on a TV screen by a miniature camera inserted through one of the four key-holes. In addition, it is sometimes necessary to perform a special X-ray during the operation called a Cholangiogram. This is used to check for stones in the bile duct.

At the end of the operation, before you wake up, all the puncture sites in your abdomen will be treated with local anaesthetic so that when you first wake up there should be very little pain. Some patients have some discomfort in their shoulders, but this wears off quite quickly.

The small cuts will all be covered with waterproof dressings.

After the procedure

You will wake up in the recovery room after your operation. You might have an oxygen mask on your face to help you breathe. You might also wake up feeling sleepy.

After this procedure, most people will have a small, plastic tube in one of the veins of their arm. This might be attached to a bag of fluid (called a drip), which provides your body with fluid until you are well enough to eat and drink by yourself.

While you are in the recovery room, a nurse will check your pulse and blood pressure regularly. When you are well enough to be moved, you will be taken to a ward.

Sometimes, people feel sick after an operation, especially after a general anaesthetic, and might vomit. If you feel sick, please tell a nurse and you will be offered medicine to make you more comfortable.

Later on after the procedure:

Is there a guarantee that keyhole surgery can be done?

No, there is no guarantee that the operation can be completed by keyhole surgery. If there is some technical difficulty with removing the gall bladder then a traditional cut would be needed to remove it. The time in hospital would be a little longer (about three to five days) and the recovery at home would be between six to eight weeks. The risk of having to convert to open surgery is small, about 1-3%.

Is there an alternative to surgery for Gall Stones?

Unfortunately no alternative exists. The only successful treatment is to remove the gall bladder and gall stones completely. The results of this operation are very good and most patients can then return to eating a normal diet.

Can I manage without my Gall Bladder?

Yes. The gall bladder is a reservoir for bile and we are able to manage without it. Rarely patients notice that their bowels are a little looser than before the operation but this is uncommon. You will be able to eat a normal diet after your operation, assuming that there is nothing else wrong with you.

Are there any risks?

Removal of the gallbladder is a very common and a very safe procedure. However, like all operations there are small risks involved. It is very important that you are fully aware of these risks as this is important in your understanding of what the operation involves. The possible complications below are particularly important as they can mean that you need to stay in hospital for longer and that further operations or procedures are required.

This is an operation to remove the gall bladder using key-hole surgical techniques.

Here are explained some of the aims, benefits, risks and alternatives to this procedure (operation/treatment).

Please ask about anything you do not fully understand or wish to have explained in more detail.

What is the Gall Bladder?

Your liver has many functions, one of which is to produce a substance called bile. This green liquid drains from the liver to the intestine via the bile duct (see diagram below). The gall bladder is a small reservoir attached to the side of the bile duct where bile can be stored and concentrated between meals. When we eat, particularly fatty foods, the gall bladder contracts and empties extra bile into the bile duct and then into the intestine to mix with the food. Bile has many functions, one of which is to allow us to absorb fat. The gall bladder sits just under the liver, which is in the right upper part of the abdomen, just under the ribs.

Why might I need my Gall Bladder removed?

Usually this is because it is giving you pain due to gall stones. These small stones form in the gall bladder and can cause a range of problems including pain, jaundice, infection and pancreatitis. They are very common but do not always cause symptoms. Gall stones that are not causing trouble can be left alone.

During the procedure (operation) itself

Before your procedure, you will be given a general anaesthetic. This is usually performed by giving you an injection of medication intravenously (i.e. into a vein) through a small plastic cannula (commonly known as ‘a drip’), placed usually in your arm or hand.

While you are unconscious and unaware your anaesthetist remains with you at all times, monitoring your condition and controlling your anaesthetic. At the end of the operation, your anaesthetist will reverse the anaesthetic and you will regain awareness and consciousness in the recovery room, or as you leave the operating theatre.

Four small holes (about 1cm long each) are made in the abdominal wall. Through these, your abdomen is inflated with carbon dioxide gas which is completely harmless.

Special long instruments are used to free up the gall bladder with its stones from underneath the liver and it is completely removed. This is all visualised on a TV screen by a miniature camera inserted through one of the four key-holes. In addition, it is sometimes necessary to perform a special X-ray during the operation called a Cholangiogram. This is used to check for stones in the bile duct.

At the end of the operation, before you wake up, all the puncture sites in your abdomen will be treated with local anaesthetic so that when you first wake up there should be very little pain. Some patients have some discomfort in their shoulders, but this wears off quite quickly.

The small cuts will all be covered with waterproof dressings.

After the procedure

You will wake up in the recovery room after your operation. You might have an oxygen mask on your face to help you breathe. You might also wake up feeling sleepy.

After this procedure, most people will have a small, plastic tube in one of the veins of their arm. This might be attached to a bag of fluid (called a drip), which provides your body with fluid until you are well enough to eat and drink by yourself.

While you are in the recovery room, a nurse will check your pulse and blood pressure regularly. When you are well enough to be moved, you will be taken to a ward.

Sometimes, people feel sick after an operation, especially after a general anaesthetic, and might vomit. If you feel sick, please tell a nurse and you will be offered medicine to make you more comfortable.

Later on after the procedure:

- Eating and drinking: You will be able to drink immediately after the operation and if this is all right and you do not feel sick, then you will be able to eat something.

- Getting around and about: After this procedure, you can get up and about as soon as you feel comfortable.

- When you can leave hospital: You will be reviewed by the doctors and nursing staff on the ward after your operation. You will be allowed home after you have had something to drink and eat. We will also check that you are not feeling sick and have been able to pass urine. You will be given a supply of simple painkillers to take home. We recommend that you take these regularly for the first couple of days at home after your operation. You may feel discomfort for seven to ten days after, but simple painkillers taken by mouth are usually all that people need to enable them to be fully mobile at home.

- When you can resume normal activities including work: Most patients return to normal activities in a matter of days following their procedure. You can drive again when you can comfortably make an emergency stop (generally about seven to ten days, but must be checked in stationary car first!). Other more vigorous activities can be resumed after two weeks as you feel comfortable.

- What happens with my dressings? All the wounds are closed with dissolvable stitches under the skin and therefore nothing needs to be done to these after the operation. Each of the wounds is covered with a small waterproof dressing which we ask you to keep intact for five days if possible. It is shower proof but will come off in a hot bath. We suggest that you get into a hot bath on day five and gently remove the dressings and leave the wound open to the air. If they rub on your clothing you may find it more comfortable to put a small Elastoplast dressing over each wound. If you have any worries about your wounds, you should contact your GP.

Is there a guarantee that keyhole surgery can be done?

No, there is no guarantee that the operation can be completed by keyhole surgery. If there is some technical difficulty with removing the gall bladder then a traditional cut would be needed to remove it. The time in hospital would be a little longer (about three to five days) and the recovery at home would be between six to eight weeks. The risk of having to convert to open surgery is small, about 1-3%.

Is there an alternative to surgery for Gall Stones?

Unfortunately no alternative exists. The only successful treatment is to remove the gall bladder and gall stones completely. The results of this operation are very good and most patients can then return to eating a normal diet.

Can I manage without my Gall Bladder?

Yes. The gall bladder is a reservoir for bile and we are able to manage without it. Rarely patients notice that their bowels are a little looser than before the operation but this is uncommon. You will be able to eat a normal diet after your operation, assuming that there is nothing else wrong with you.

Are there any risks?

Removal of the gallbladder is a very common and a very safe procedure. However, like all operations there are small risks involved. It is very important that you are fully aware of these risks as this is important in your understanding of what the operation involves. The possible complications below are particularly important as they can mean that you need to stay in hospital for longer and that further operations or procedures are required.

- Leakage of bile – When the gallbladder is removed, special clips are placed on the tube that connects the gallbladder to the main bile duct draining the liver. Despite this, sometimes bile fluid leaks out. If this does occur, we have a number of different ways of dealing with this. Sometimes the fluid can simply be drained off by our colleagues in the X-ray department. In other cases a special type of endoscopy called an ERCP is necessary. This is a procedure where you are made very sleepy (using sedative injections) and a special flexible camera (‘an endoscope’) is passed down your gullet and stomach to allow the doctor to see the lower end of your bile duct. The doctor then injects a special dye that allows them to see where the bile has leaked from. If they see where the bile is leaking from, they will insert a plastic tube (called a ‘stent’) into your bile duct to allow the bile to drain internally. This stent is usually removed six to eight weeks after it is put in. Rarely, if a patient develops a bile leak, an operation is required to drain the bile and wash out the inside of the abdominal cavity. This can usually be performed as a keyhole procedure.

- Injury to Bile Duct – Injury to the main bile duct draining bile from the liver to your intestine is a rare (1 per 400 cases) complication of gallbladder surgery. We use a number of techniques during the operation to prevent this happening. If an injury occurs, it requires immediate repair so that you recover smoothly from the operation. Repair of this injury requires an open cut to be made under your ribs.

- Stones in the Bile Duct – Rarely, stones may be discovered that have moved out of the gall bladder into the bile duct. Sometimes it is possible to remove these at the time of operation; however, sometimes this is not possible. An ERCP test (as described above) may later be required to remove the stones.

- Injury to intestine, bowel and blood vessels – Injury to these structures can, very rarely, occur during the insertion of the keyhole instruments and during the freeing up of the gallbladder particularly if it is very inflamed. Usually this injury can be seen and repaired at the time of the operation, but occasionally may only become clear in the early postoperative period. If it is suspected that you may have sustained such an injury, a further operation will be required. This will be performed as a keyhole operation but will need conversion to an open operation if necessary.

- Bleeding – this very rarely occurs after any type of operation. Your pulse and blood pressure are closely monitored after your operation as this is the best way of detecting this potential problem. If bleeding is thought to be happening, you will require a further operation to stop it. This can usually be done through the same keyhole scars as your first operation.

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolus - All surgery carries varying degrees of risks of thrombosis (clots) in the deep veins of your leg. In the worst case a clot in the leg can break off and travel to the lung (pulmonary embolism). This can significantly impair your breathing. To prevent these problems around the time of your operation and following your operation we give you some special injections to ‘thin’ the blood. We also ask you to wear compression stockings on your legs before and after surgery and also use a special device to massage the calves during the surgery. Moving about as much as you can, including pumping your calf muscles in bed or sitting out of bed as soon as possible reduce the risk of these complications.

- Wound haematoma - Bleeding under the skin can produce a firm swelling of blood clot (haematoma), this may only become apparent several days after the surgery. It is essentially a bruise. This may simply disappear gradually or leak out through the wound without causing any major consequences to you.

- Wound Infection – This affects your scars (‘wound infection’). If a wound becomes red, hot, swollen and painful or if it starts to discharge smelly fluid then it may be infected. It is normal for the wounds to be a little sore, red and swollen as this is part of the healing process and represents the body’s natural reaction to surgery. It is best to consult your doctor if you are concerned. A wound infection can happen after any type of operation. Simple wound infections are easily treated with a short course of antibiotics.

- Deep Infection – A rarer and more serious problem with infection is where an infection develops inside your abdomen or chest cavity. This will often need a scan to diagnose, as there may be no obvious signs on the surface of your body. Fortunately, this type of problem will usually settle with antibiotics. Occasionally, it may be necessary to drain off infected fluid. This is most frequently performed under a local anaesthetic by our colleagues in the X ray department. In the worst case scenario a further operation is required to correct this problem.

- Scarring – Any surgical procedure that involves making a skin incision carries a risk of scar formation. A scar is the body’s way of healing and sealing the cut. It is highly variable between different people. All surgical incisions are closed with the utmost care, usually involving several layers of sutures. The sutures are almost always dissolvable and do not have to be removed. The larger an incision the more prominent it will be. Despite our best intentions, there is no guarantee that any incision (even those only 1-2 cm in length) will not cause a scar that is somewhat unsightly or prominent. Scars are usually most prominent in the first few months following surgery, however, tend to fade in colour and become less noticeable after a year or so.

- Other complications – Those described are the most common and serious complications that may occur following this surgery. It is not possible to detail every possible complication that may occur following any operation. If another complication that you have not been warned about occurs, we will treat it as required and inform you as best we can at the time. If there is anything that is unclear or risks that you are particularly concerned about, please ask.